22. Juli 2020 – Policy Brief

Summary of problem

The people of Switzerland have done their part to help flatten the curve of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. To maintain a more open public environment, appropriate behaviors of the population and joint responsibility remain critical. This situation requires significant and sustained protective behaviors by every person and every organization. To guide and inform behaviors, effective communication strategies must be integrated into the pandemic response. SARS-CoV-2 is characterized by scale, novelty, uncertainty, regional variation, societal, health, and economic effects. Multiple communication sources and messages in a complex setting can facilitate confusion, complacency, or even distrust among the population, resulting in lower adoption of protective behaviors, individualism and thus, risk of increased cases. Moving forward, there are new challenges for communication strategies. Consideration of communication options and evidence can form part of an effective “Swiss model” of the SARS-CoV-2 response that heavily relies on the population’s behaviors and the commitment to joint responsibility.

Questions

- Why is effective communication critical?

- What are the current needs and priorities for communication?

- What factors are associated with message receptivity and behavioral compliance?

Question 1. Why is effective communication critical?

Communication plays a central role in successful management of emergencies. The primary objective of most emergency communication is to influence behavior, with the goal of reducing and minimizing the duration and the impact (Azizi et al., 2020; Jardine et al., 2015; Seeger et al., 2018). Accordingly, the public is reliant on information, knowledge, opportunities, and guidance from government and public authorities to inform their behaviors. However, communication that focuses on providing mainly “information” and less on actionable steps to engage in the recommended behavior results in a public that may “know”, but does not “understand how to”, thus reducing behavioral adherence with protective measures (Sellnow et al., 2017).

“Good communication practices will not substitute for bad planning, uninformed policies, or misconceptions about vulnerable populations (e.g., they are homogeneous, ignore public health messages, view pandemic flu as a remote threat, and lack the knowledge, ability, or will to change behavior). However even the best strategies can be rendered ineffective by inadequate health risk communications or failure to integrate a communication perspective and community engagement at every stage of planning, response, and recovery.” (Vaughan & Tinker, 2009)(p S324)

Perhaps the most meaningful distinction between emergency crisis communication and other types of communication is the urgency of action required, at the scale required, and in an environment of evolving circumstances (S. T. Lee & Basnyat, 2013; Liu et al., 2017). Communication must stress urgency and diligence in actions, be personally relevant for every resident, and be trusted. Communications must also acknowledge the considerable uncertainty about the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the quick pace of scientific research (see WHO “The evolution of science and our role in preventing the spread of COVID-19”).

Public understanding and actions cannot be taken for granted. A recent report of Swiss public opinion suggests that about 41% of Swiss residents lack enough information about the pandemic, the measures, and associated behaviors (Bosshardt & et al, 2020b). Confidence in political leadership remains higher than many countries with ~62% trusting government in May and ~66% in June (Bosshardt & et al, 2020a), yet willingness to install and use the SwissCovid App has declined, with 54% supporting it in June, down from 65% in April (SRF, 2020).

Communication campaigns need to be targeted for specific regions, populations, and situations

Given that the pandemic does not homogenously and as a wave affect our country, there is substantial regional variation in opinions about the pandemic and these perspectives change over time. Differences in views on the timeline of relaxing measures, mask wearing, border control, and travel show that people in the hardest hit Cantons favor a more slow and cautious relaxing and stronger focus on protective measures (e.g., mask wearing). (Bosshardt & et al, 2020b). For example, some cantons have recently tightened some measures and changed messaging to reflect the need to protect both self and others (currently: Basel-Stadt, Solothurn, Aargau, Ticino, Vaud, Jura, Valais). Targeted campaigns for cross-border commuters are also needed at border locations (see NCS-TF Policy Brief “SARS-CoV-2 prevention in Switzerland and open borders from 15 June 2020 onwards” last updated 13.07.2020).

The behavior of individuals has a strong influence on transmission, and focused communication campaigns can be used as a fast response to increasing case numbers. In the NCS-TF Policy Brief “Strategy to react to substantial increases in the numbers of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Switzerland” (08.06.2020), we stress that to achieve the goal of preventing a nationwide second wave, “we need a maximally efficient, well-coordinated and targeted strategy of surveillance and response”, i.e. to detect local outbreaks, foci or transmission, early in order to act in a tailored manor with measures specific for the respective outbreak setting (e.g. elderly homes, service- and production settings, night clubs, sports and community settings) . “We also need a continued participation of the general population in the adoption of [the basic] preventive measures.” And that we need “Intensified and targeted communication.”

Question 2. What are the needs and priorities for communication now?

Switzerland is in a relatively good situation because we all took collective action, but this can change.

Effectively communicate the outcomes achieved from preventive actions. The prevention paradox occurs when measures “can achieve large overall health gains for whole populations but might offer only small advantages to each individual. This leads to a misperception of the benefits of preventive advice and services by people who are apparently in good health(2,3)”(G. Rose, 1981, 2001; World Health Organization, 2002) (p. 147)”. While difficult to convey, this is the case in Switzerland: people behaved, we saved lives and the economy, and this “Swiss Model” is one that Switzerland can be proud of achieving. However, the virus is not gone.

The public needs to understand that we have to find ways to ‘live with the virus’ and minimize its consequences, i.e. living with a highly infectious virus that has no cure or vaccine yet. Communicators need to make sure that they explain clearly and convincingly the importance of the core individual and public health measures. The basic protective behaviors, hygiene, masks, and physical distancing are the critical actions that individuals can take to prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The Test-Trace-Isolate-Quarantine (TTIQ) plan is at the core of the surveillance-response strategy to detect outbreaks and foci of transmission early and prevent nationwide second waves.

The need for effective surveillance and response, so we can have local, targeted reactions.

A fast and targeted approach tailored to the outbreak setting is the effective public health and economic response. As measures are relaxed and more people gather in common spaces, concern about an increase in the number of SARS-CoV-2 cases grows. A large and rapid increase in the number of infections will require Switzerland to go into lockdown again. Effective surveillance and response are needed to prevent a nationwide lockdown. TTIQ allows for early detection and prevention of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and contact tracing is a key activity to contain transmission, especially when case numbers are low. Outbreaks will likely happen in clusters. Communities that can react fast can slow the spread without affecting the whole country.

Rapid and effective local responses require communication that achieves public understanding of the importance and value of testing and contact tracing. People need to know when to seek a test, where to get a test, who pays for testing, what testing means for them (rights, obligations, and protections) and the ways in which both classical and digital proximity tracing help to slow the spread of coronavirus. People also need to know why it matters to them and others, believe it is worthwhile and that any consequence is smaller than the impact of the virus. This includes knowing legal protections for having to isolate or quarantine. This is achievable, as illustrated by the acceptance and adoption of the Swiss Night Pass in some cantons which provides contact tracing information for all those who enter night clubs (web24.news, 2020).

The importance of prevention and behaviors of the population.

The basic protective, preventative behaviors heavily promoted in the early phase of this pandemic remain of paramount. Communicators need to repeat messages and explanations about the need to maintain hand hygiene, mask-wearing and physical distancing to avoid resumption of more stringent measures or introduction of new measures (Moore et al., 2020). The measures in place now are extremely cost-efficient and socially better than a national or regional lockdown. Thus, preventing further broad lockdowns, nationally or where outbreaks occur, requires vigilance.

Communicators must make messages clear and convincing, highlighting the social norm and expectation that physical distancing of at least 1.5-2 meters, frequent hand washing, mask wearing, and hygiene rules for coughing and sneezing are expected. But information is not enough, communication must persuade people by being provided by trusted sources (i.e., authorities, experts, leaders of firms, schools, associations and clubs, but also members of the public and target populations themselves) that highlights facts, risks, benefits, and show how to do, and the risks (to self and others) of not performing behaviors properly. Modelling behaviors from trusted sources and authority figures builds trust, acceptance, and adoption, as does the public feeling appreciated for the role they play. This can be stressed through communications and actions.

Due to the evolving science combined with the supply chain, the protective behavior of mask wearing in public spaces where physical distancing cannot be maintained is reiterated and now strongly advised. The population needs to know why and which masks work, how to know if a mask meets basic criteria for protection, how to wear them properly, how to dispose of them, and that they protect others (see NCS-TF PB “Benefits of wearing masks in community settings where social distancing cannot be reliably achieved” (02.07.2020)). When mandated, as they are on public transport and in shops in some cantons, enforcement must be strong and consistent. Thus, those who must enforce as well as those who must comply, need to trust the science about masks and trust that the measure protects both self and others, for the mutual benefit of health, economy, and society.

These preventive and protective behaviors have societal implications, as without them the most vulnerable or risk aversive are double burdened: once by the virus and once by their community that does not protect them. This virus can only be contained with collective action and hence it is important to effectively communicate the societal duty and collective responsibility to diligently engage in protective behaviors that facilitate more equality. Freedoms are critical, but that includes other persons freedom to enjoy the relaxed measures without being infected by those not behaving properly.

The most pressing current communication priorities include:

- A second nationwide wave is not inevitable across Switzerland. It can be prevented with the current basic preventative measures, TTIQ and thus the surveillance and response strategy that will identify and confine local outbreaks and transmission foci

- Living with the virus means having all the measures in place, but that we will still encounter infections

- There could be an increased rate of hospitalizations and still people getting sick and dying from Covid-19, especially in fall and winter when overall respiratory infections and influenza will be more prevalent. This should not be accepted as inevitable. Mitigation of transmission will be essential

- The SARS-COV-2 case numbers do not tell the full story of the coronavirus burden, as infection is not equal to mortality. Some people tend to see infection as being equal to mortality. As the death rate for the non high-risk population is low there is a risk of people becoming complacent, while at the same time becoming doubtful of the implemented control measures which they can view as exaggerated. As this risks increased spread of the virus and loss of well-needed trust in public health authorities, it is important to be transparent about the risk of severe disease for different risk groups

- The focus must be on foci of transmissions so that action in both measures and communication are tailored to the local circumstances

- The need for local responses, afforded by good and rapid surveillance and data sharing, and strong support to localize such communication

- People need to have extreme discipline to avoid tightening of measures, including a possible regional lock downs

- Respecting the physical distance between people and hygiene regulations are of paramount

- Wear a mask appropriately if you cannot maintain physical distance

- The utility of Testing, Tracing, Isolation, and Quarantine in keeping the economy and society functioning

- Download and use the SwissCovid app to allow more effective TTIQ

- Situations with a high risk of transmission should be avoided. These situations include in particular indoor events that do not allow people to keep their distance from each other and wear masks

- When participating in any event, official or informal, strictly observe the hygiene and distance regulations, especially when it is difficult to trace contacts effectively

- Air indoor premises regularly to reduce the risk of transmission

- Young adults are proving to be infectious and need to be diligent in SD, mask and hygiene behaviors

- Young adults constitute a group particularly vulnerable to the economic consequences of the epidemics, should it continue to affect business

- The fundamentals in viruses, spread of viral infections, and novel viruses

- From an economic point of view, an extensive testing and tracking strategy is very cost-efficient as it not only reduces infections, but it is also beneficial for the economy. Targeted and well communicated measures and thus avoidance of large regional or national lockdowns can at the same time save lives and limit economic losses

- The science about the virus is evolving, and thus recommendations will also evolve and can be refined to reflect the science. This is both expected and proper.

Question 3. What factors are associated with message receptivity and behavioral compliance?

The literature shows consistency on message development processes and key variables influencing behaviors.

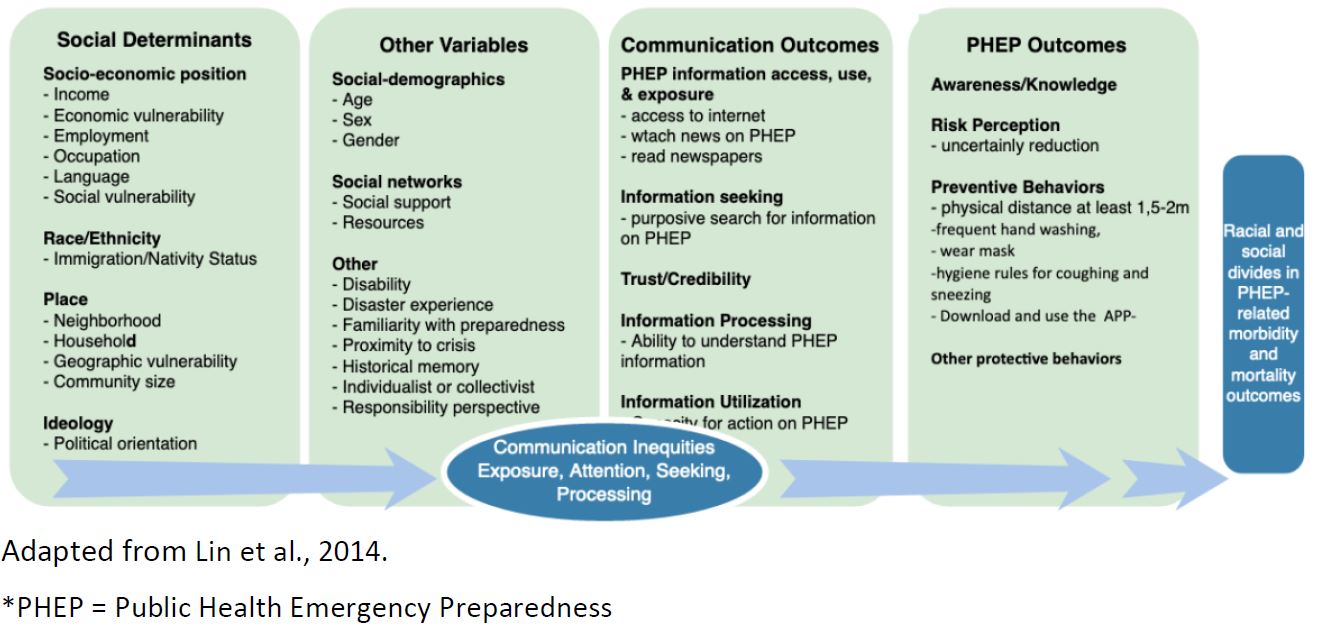

Receptivity of messages requires that communication is relevant, clear, understandable, and delivered through trusted and commonly accessed channels and sources (Lin et al., 2016). Persuasive messages are more effective in motivating individuals to comply than fear-based messages, especially when messages are not tailored at the individual level (Liu et al., 2017). Building and maintaining trust is vital to the effectiveness of communication but it can be weakened by message delivery, content, individual experiences with public health emergencies, and individual beliefs and values. Targeting messages, delivery channels, and message source to population segments is important (Hoda, 2015; Hou et al., 2018) Individual responses to communication are shaped by an interaction of personal, contextual and cognitive factors and it is extremely important to identify them and incorporate such information into communication, including who delivers the message (Vaughan & Tinker, 2009). Understanding local needs for communication and using those insights to design messages and select messengers and channels is associated with improved behavioral compliance (Holmes et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2014; Novak et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2018). This is also relevant as the pandemic progresses and measures change, as trust in sources, especially government, changes throughout the crisis as well as willingness to adhere to measures (Henrich & Holmes, 2011; Lachlan et al., 2014). Communicating uncertainty about aspects of public health emergencies to the public helped to reduce uncertainty about protective behaviors and minimized the damaging effects of misinformation.

Key variables associated with behavioral compliance to protective measures include: trust, risk perception, perception of responsibility to contribute as an individual to a community problem, perceived disease severity, information seeking, level of worry, knowledge about the disease, self-efficacy, timing, transparency, exposure to credible media sources, and experience with a pandemic (Bults et al., 2011; Cordova-Villalobos et al., 2017; de Zwart et al., 2009; Holmes et al., 2009; Hou et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2014, 2016; Maduz et al., 2019).

Trust includes: in public officials, that the source is credible, that the promoted measure will achieve the results (i.e., outcome expectancy), and that they can perform the behavior (self-efficacy). For example, Hou et al., 2018 found “during the outbreak of SARS, knowledge level on the disease itself was not associated with adoption of preventive measure but public trust was.”. In the Dutch study of Bults et al 2011, self-efficacy (trust in one’s self) was the largest predictor variable. Sharing of personal data (such as needed for digital or classical contact tracing), predictors include a sense of social duty, having some self-benefit and understanding the public good is being served (Skatova & Goulding, 2019). Public trust in science and public health authorities also promotes data sharing (Aitken et al., 2016).

The underlying and overarching focus of communications and actions must illustrate the necessity of collective action to contain SARS-CoV-2. This crisis can only be solved together, as a community and society. Each person in Switzerland is part of the social tissue that makes this country what it is. Communication needs to remind people and firms of this stressing the actions help both self and others needed to contain the virus, and thus keep health, economy, and society prosperous.

Social determinants of health behavior and communication accessibility are associated with behavioral compliance (M. Lee et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2014). Lower socio-economic status is associated with knowledge of health emergency (Hou et al., 2018) and “lower levels of awareness and knowledge regarding pandemics, leading to poorer behavioral responses when dealing with an outbreak” (Lin et al., 2016). Further, “social and individual determinants (i.e. education, income, race/ethnicity) may lead to inequalities in individual or group-specific exposure to public health communication messages, and in the capacity to access, process, and act upon the information received by specific sub-groups- a concept defined as communication inequalities”. (Lin et al., 2014). Thus, communication must be pushed to people where they are, rather than relying on pull mechanisms.

Channels of communication need to reflect what all people in Switzerland use and trust for SARS-CoV-2 related information; which means TV, radio, and newspapers, which are perhaps the most important channels of information during emergency situations (Holmes et al., 2009; Hou et al., 2018; Jardine et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2014; Sjöberg, 2018). Other channels matter, but are often secondary in pandemic situations. For example, the nationally representative online survey in Switzerland (N=758) during 2017, ICT sources were preferred by 32% of the sample although 86% indicated that they used official information sources for information. (Maduz et al., 2019).

In summary: To increase compliance with recommended protection measures the evidence suggests:

- Provide clear, consistent, understandable, actionable, trustworthy information that buildsself-efficacy and responsibility of the target audience and that is accessible and done sothrough mass media sources and well as social and online channels used by target audiences

- Segment and target audiences for communication. One size messaging will not fit all;targeting and tailoring are key

- Focus on mass public, but also targeted communications for those behaving sub-optimally orat higher risk of infection by using messages that resonate and messengers that are trusted byeach target population

- Listen to people and react accordingly. Engage in two-way communication so that messagesand measures reflect the reality of all population groups. This includes listening to needs andconcerns and using this to inform communication messages and delivery options. Peoplemust know and believe that they are being “heard” regarding all of their challenges caused bySARS-CoV-2, beyond the threat of infection.

- To build trust and self-efficacy, show and explain “how to do” and that all can contribute andnot only “what to do” and “why it matters” (pros and cons).

- Also to build trust, policy and public health must take the broader societal implications of theepidemic and the restrictions very seriously.

- Highlight the benefit to self and others.

- Utilize traditional channels, including TV and newspapers, to communicate

- Approach communication from an egalitarian basis, and thus make efforts to reachpopulations who are allophones, less connected online, or disabled.

- Increase accessibility of communications delivered to the mass public, such as including sign-language in press conferences, TV adverts, online videos, and making materials accessible fordifferently abled persons, people with low literacy, low vision, low hearing, who speak non-Swiss languages.

- Do not take for granted that the public understands and believes the message. Pretestmessages with target groups

- As measures change, what remains important must be stressed, not just what is new

- Congratulate and thank the population for the what they have accomplished together, asconcretely as possible (what actions they did with what benefit) without conveying it is ok torelax protective behaviors.

Aitken, M., de St. Jorre, J., Pagliari, C., Jepson, R., & Cunningham-Burley, S. (2016). Public responses to the sharing and linkage of health data for research purposes: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Medical Ethics, 17(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-016-0153-x

Azizi, A., Montalvo, C., Espinoza, B., Kang, Y., & Castillo-Chavez, C. (2020). Epidemics on networks: Reducing disease transmission using health emergency declarations and peer communication. Infectious Disease Modelling, 5, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idm.2019.11.002

Bosshardt, L., & et al. (2020a). Monitoring der BevölkerungDie Schweiz und die Corona-Krise (p. 66). Sotomo. https://sotomo.ch/site/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/SRG_sotomo_Monitoring_Coronakrise_W3_web.pdf

Bosshardt, L., & et al. (2020b). Monitoring der BevölkerungDie Schweiz und die Corona-Krise (p. 71). Sotomo. https://sotomo.ch/site/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/SRG_sotomo_Monitoring_Coronakrise_W4.pdf

Bults, M., Beaujean, D. J., de Zwart, O., Kok, G., van Empelen, P., van Steenbergen, J. E., Richardus, J. H., & Voeten, H. A. (2011). Perceived risk, anxiety, and behavioural responses of the general public during the early phase of the Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands: Results of three consecutive online surveys. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-2

Cordova-Villalobos, J. A., Macias, A. E., Hernandez-Avila, M., Dominguez-Cherit, G., Lopez-Gatell, H., Alpuche-Aranda, C., & Ponce de León-Rosales, S. (2017). The 2009 pandemic in Mexico: Experience and lessons regarding national preparedness policies for seasonal and epidemic influenza. Gaceta Medica De Mexico, 153(1), 102–110.

de Zwart, O., Veldhuijzen, I. K., Elam, G., Aro, A. R., Abraham, T., Bishop, G. D., Voeten, H. A. C. M., Richardus, J. H., & Brug, J. (2009). Perceived Threat, Risk Perception, and Efficacy Beliefs Related to SARS and Other (Emerging) Infectious Diseases: Results of an International Survey. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 16(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-008-9008-2

Henrich, N., & Holmes, B. (2011). What the Public Was Saying about the H1N1 Vaccine: Perceptions and Issues Discussed in On-Line Comments during the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic. PLoS ONE, 6(4), e18479. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018479

Hoda, J. (2015). Identification of information types and sources by the public for promoting awareness of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia. Health Education Research, cyv061. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyv061

Holmes, B. J., Henrich, N., Hancock, S., & Lestou, V. (2009). Communicating with the public during health crises: Experts’ experiences and opinions. Journal of Risk Research, 12(6), 793–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669870802648486

Hou, Y., Tan, Y., Lim, W. Y., Lee, V., Tan, L. W. L., Chen, M. I.-C., & Yap, P. (2018). Adequacy of public health communications on H7N9 and MERS in Singapore: Insights from a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 436. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5340-x

Jardine, C. G., Boerner, F. U., Boyd, A. D., & Driedger, S. M. (2015). The More the Better? A Comparison of the Information Sources Used by the Public during Two Infectious Disease Outbreaks. PLOS ONE, 10(10), e0140028. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140028

Lachlan, K. A., Spence, P. R., & Lin, X. (2014). Expressions of risk awareness and concern through Twitter: On the utility of using the medium as an indication of audience needs. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 554–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.029

Lee, M., Ju, Y., & You, M. (2019). The Effects of Social Determinants on Public Health Emergency Preparedness Mediated by Health Communication: The 2015 MERS Outbreak in South Korea. Health Communication, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1636342

Lee, S. T., & Basnyat, I. (2013). From Press Release to News: Mapping the Framing of the 2009 H1N1 A Influenza Pandemic. Health Communication, 28(2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2012.658550

Lin, L., McCloud, R. F., Bigman, C. A., & Viswanath, K. (2016). Tuning in and catching on? Examining the relationship between pandemic communication and awareness and knowledge of MERS in the USA. Journal of Public Health, fdw028. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdw028

Lin, L., Savoia, E., Agboola, F., & Viswanath, K. (2014). What have we learned about communication inequalities during the H1N1 pandemic: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 484. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-484

Liu, B. F., Quinn, S. C., Egnoto, M., Freimuth, V., & Boonchaisri, N. (2017). Public Understanding of Medical Countermeasures. Health Security, 15(2), 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2016.0074

Maduz, L., Prior, T., Roth, F., & Käser, M. (2019). Individual Disaster Preparedness: Explaining disaster-related Information Seeking and Preparedness Behavior in Switzerland (p. 34 p.) [Application/pdf]. ETH Zurich. https://doi.org/10.3929/ETHZ-B-000356695

Moore, K. A., Lipsitch, M., Barry, J. M., & Osterholm, M. T. (2020). COVID-19: The CIDRAP Viewpoint. Regents of the University of Minnesota.

Novak, J., Day, A., Sopory, P., Wilkins, L., Padgett, D., Eckert, S., Noyes, J., Allen, T., Alexander, N., Vanderford, M., & Gamhewage, G. (2019). Engaging Communities in Emergency Risk and Crisis Communication: Mixed-Method Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research, 2(1), 61–96. https://doi.org/10.30658/jicrcr.2.1.4

Rose, G. (1981). Strategy of prevention: Lessons from cardiovascular disease. BMJ, 282(6279), 1847–1851. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847

Rose, G. (2001). Sick individuals and sick populations. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30(3), 427–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.3.427

Seeger, M. W., Pechta, L. E., Price, S. M., Lubell, K. M., Rose, D. A., Sapru, S., Chansky, M. C., & Smith, B. J. (2018). A Conceptual Model for Evaluating Emergency Risk Communication in Public Health. Health Security, 16(3), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2018.0020

Sellnow, D. D., Lane, D. R., Sellnow, T. L., & Littlefield, R. S. (2017). The IDEA Model as a Best Practice for Effective Instructional Risk and Crisis Communication. Communication Studies, 68(5), 552–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2017.1375535

Sjöberg, U. (2018). It is Not About Facts – It is About Framing. The App Generation’s Information-Seeking Tactics: Proactive Online Crisis Communication. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 26(1), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12145

Skatova, A., & Goulding, J. (2019). Psychology of personal data donation. PLOS ONE, 14(11), e0224240. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224240

SRF. (2020). Die Angst vor dem Coronavirus verfliegt: 4. Corona-Umfrage der SRG. http://www.srf.ch/news/schweiz/4-corona-umfrage-der-srg-die-angst-vor-dem-coronavirus-verfliegt

Vaughan, E., & Tinker, T. (2009). Effective Health Risk Communication About Pandemic Influenza for Vulnerable Populations. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S2), S324–S332. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.162537

web24.news. (2020, September 7). Jurassic nightclubs adopt the Swiss Night Pass. https://www.web24.news/u/2020/07/jurassic-nightclubs-adopt-the-swiss-night-pass.html

World Health Organization. (2018). Managing epidemics: Key facts about major deadly diseases. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=1865300

World Health Organization, W. H. (2002). The world health report 2002: Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. World Health Organization.

Date of request: 8/7/2020

Date of response: 22/7/2020

In response to request from: NCS-TF

Comment on planned updates: regularly; depending on course of pandemic

Expert groups and individuals involved: All, with Public Health group in lead

Contact persons: L. Suzanne Suggs (suzanne.suggs@usi.ch) and Marcel Tanner (marcel.tanner@swisstph.ch)